May 31 is Dam Safety Awareness Day

Who ever heard of this holiday?

Maybe the people who live near the 90,000 or so dams in the United States! (BTW, Texas has more dams than any other state, followed by Kansas . . .)

Maybe the people who live near the 90,000 or so dams in the United States! (BTW, Texas has more dams than any other state, followed by Kansas . . .)

Most likely to have heard about Dam Safety Awareness Day, however, are the people who live near the 17% of all dams that are considered by the American Society of Civil Engineers as having high-hazard potential!

Apparently the Oroville Dam in northern California, that came so close to collapsing this spring, was not even on that list . . .!

(Personal note. My dad, who among other things was a road-grader operator – “Best damn blade-man west of the Mississippi” – worked on the construction of the Oroville Dam in the 60s.)

The Oroville Dam didn’t collapse, thanks to quick action by its operators. But in the aftermath, it was discovered that its Emergency Action Plan had never been tested in the 50-year-life of the dam. And during that time, population in the area below the dam had doubled and evacuation options had changed. Officials admitted that had the dam actually broken, citizens would not have received a warning quickly enough to be able to get to safety.

What makes a high-hazard dam?

The ASCE defines it this way: “A dam in which failure or mis-operation is expected to result in loss of life and may also cause significant economic losses, including damages to downstream property or critical infrastructure, environmental damage, or disruption of lifeline facilities.”

And, the ASCE gives a grade of D to our dam infrastructure.

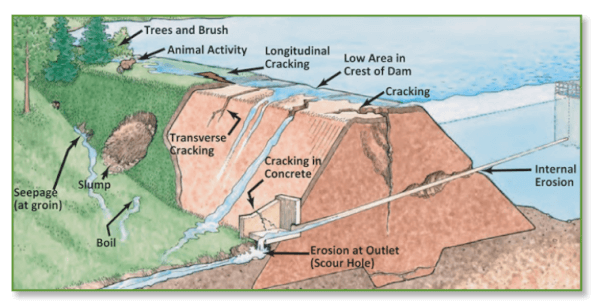

What risks do dams face?

Most dams become at risk simply because of age and lack of maintenance. This image from FEMA shows the kinds of weaknesses that appear as an embankment dam ages:

At the Oroville site, the problem wasn’t in the main embankment, but rather a break in the emergency spillway. When water was released to relieve pressure on the main dam, the spillway began to give way, which could have led to the whole thing collapsing.

Too much water behind the Oroville Dam was caused by unexpectedly heavy rain storms. But dam failures are not always caused by storm. Most are caused by settlement and damage from earthquakes, mechanical failures (like gates not working) and poor design (allowing for overtopping and blocking by debris).

So who is keeping track of whether dams are safe?

States regulate the vast majority of dams in the U.S. (about 80%). The Federal government regulates the remaining number.

Regulation is one thing. Actually doing the required maintenance is another. Most states’ safety programs are woefully underfunded and do not have any authority to require maintenance.

Keeping the dams safe is up to dam owners. And nearly 70% of dams are privately owned.

For example, a homeowners’ association that wants its homes built around a lake will own and operate a dam. A utility may own a lake used for water storage or for electricity production. And, of course, large commercial entities (agricultural, mining, etc.) may build waste holding ponds behind dams.

As more dams are built, as downstream development continues, and as ALL dams age, the number of high-risk dams increases.

Where are these dangerous dams?

I tried to find a map showing dams and danger areas – called Dam Break Inundation Areas. It wasn’t easy!

What I finally discovered is the National Inventory of Dams, maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers. As a “non-government user” I could get into the database but even after I filtered for my own state, the data wasn’t easy to read. And I never found a map!

I encourage you to check it out yourself: https://nid.usace.army.mil If you have the name of a specific dam, you’ll get info faster.

Another course would be to inquire of your own insurance agent. You may have to shop for a specialist in flood insurance to get specifics for your own location.

Obviously, even if you personally are not in the path of water from a breech, you could be impacted in other ways by the failure of a dam.

Homes and businesses of people you know might be flooded; those people might be displaced. Your personal water supply might be shut off. Water for irrigation, fighting fires, etc. – all might be reduced. Utilities that depend on hydro power could be affected. Transportation systems could be disrupted.

If we are near a dam, what should we be doing in the way of emergency planning?

1- People: Somebody manages that dam! Find out who, and ask these questions:

- Who owns the dam? Has it been inspected?

- Is there an Emergency Action Plan for the dam?

- When was it last updated?

- What kinds of warning systems are in place to warn us of danger or potential danger? (Sirens, reverse 911 calls, door-to-door notification?)

- Are evacuation routes laid out?

- What about people with disabilities?

2-Political: If you encounter barriers or obfuscation (love that word when it comes to things political!), consider these actions:

- Urge your state to require a disclosure of whether property for sale is in an inundation zone.

- Likewise, urge policymakers to require disclosure of dam-related issues to potential owners of dams and property around them.

- Urge legislators to fund dam safety programs and to provide funding for those programs.

3-Personal: And everyone can add to their own personal emergency plan:

- An evacuation route to higher ground.

- How to evacuate family members who need assistance.

- Practice evacuation route and point out a family meeting place.

Having an evacuation kit packed and ready to go is a given.

Want more info for your family or your group?

FEMA has produced a useful fact sheet (8 pages), available here:

Hope this has added to your knowledge about the (often invisible) world around us!

Virginia

Your Emergency Plan Guide Team

P.S. And the story behind the Dam Safety Awareness Day being on the 31st . . .

One of the worst disasters in U.S. History was the Johnstown flood of 1889, which happened on May 31.

At that time, Johnstown was a thriving community in western Pennsylvania. Nearby, a group of wealthy citizens had restored an old dam and created a private lake for fishing, sailing and ice boating.

In May the area experienced several days of extraordinary rain, and it was feared the dam would collapse. Nothing could be done, however, in part because debris had built up in the spillway, making it impossible to lower the level in the dam. Warnings were issued, but false alarms had been given before, so residents ignored them.

At 4 p.m. on the 31st, the dam was overtopped, and collapsed, sweeping a 20-ft. high wall of trees, railcars and entire houses down the valley toward Johnstown. There, the mass was stopped by a bridge, which became a second barrier, causing the water to back up and cover the whole town. Then, everything burned.

More than 2,200 people died in the Johnstown flood. The entire town was destroyed, and surrounding communities dealt with typhus, smoke, contaminated water supplies and outbreaks of violence.

The private club members and dam owners were able to claim the dam break was “an act of God” and escaped being held liable.